Plant patents are getting to be ubiquitous. They’re meant to protect the time and effort put into breeding new plants, but are there unintended consequences?

Plant patents are granted to those who discover or invent a new and distinct cultivar and asexually reproduce it. Plant patents allow the patent holder to prevent others from asexually reproducing the new plant without first entering into a licensing agreement. Plant patents last for 20 years. Patent lifespan is particularly relevant for trees, given that they may not gain market share as quickly as shrubs, which develop their highly marketable characteristics in a shorter period of time than trees, and those desirable attributes are often visible at the point of sale.

Some of the requirements for receiving a plant patent:

The plant can be produced asexually.

The plant was invented or discovered, and if discovered, it was in a cultivated area (not the wild)

The part of the plant used for asexual reproduction is not a tuber food part (e.g., potato, Jerusalem artichoke).

The person, company or nonprofit entity filing the patent invented or discovered the plant and asexually reproduced it.

The plant has not been patented, in public use or for sale, or otherwise available to the public more than one year prior to the effective filing date.

The plant is novel and has at least one inherent, distinguishing characteristic (i.e., beyond that which is induced by varying environmental conditions).

The entirety of the plant is protected, but not the reproductive subparts of the plant (i.e., seeds, flowers and fruit are not protected by plant patents) such that patented plants can be used by other plant breeders to produce new hybrids.

The key: Asexual reproduction.

A plant can be patented only if can be reproduced asexually. Asexual reproduction produces plants that are genetically identical to the parent plant because no mixing of male and female gametes takes place. The patent then prohibits any further asexual reproduction of the plant without a license.

Asexual reproduction can take place by natural or artificial (assisted by humans) means. Natural asexual reproduction takes place without seeds or spores - for example by means of stolons or rhizomes. That’s fine for letting them spread through your garden, but isn’t very practical for larger scale propagation.

Asexual reproduction methods:

Grafting produces plants by combining favorable stem characteristics with favorable root characteristics. The stem of the plant to be grafted is known as the scion, and the root is called the stock.

Stem Cuttings produce plants by placing a portion of the stem containing nodes and internodes that have been treated with rooting hormone into moist soil and allowing them to root.

In layering, a part of the stem is buried so that it forms a new plant.

Micropropagation (also called plant tissue culture) is a method of propagating a large number of plants from a single plant in a short time under laboratory conditions. A part of the plant such as a stem, leaf, embryo, anther, or seed can be used to start tissue culture propagation. Under sterile conditions, the plant material is placed on a plant tissue culture medium that contains all the minerals, vitamins, and hormones required by the plant. The plant part gives rise to individual plantlets. These can be separated and are first grown under greenhouse conditions before they are moved to field conditions.

The process of making“new plants” has a few key steps:

Breeding: Breeding is a series of decisions based on either defined crosses or collecting seed from open-pollinated plants. After collecting seed, the breeder evaluates seedlings to see if they have something that’s interesting or characteristics that they are looking for.

Evaluation and Selection: Breeders have many things they’re looking for, including habit, flower color, flower quality, bloom time, foliage color and many more. The selection process narrows the choices down to a more manageable number - the chosen seedlings have to be propagated so that they can be grown in trial gardens and evaluated for their performance. Some breeders have their own propagation facilities - using either tissue culture or cuttings - but there are also growers who team up with breeders to propagate promising new plant choices.

This is a years-long process, often involving a minimum of 4 years of trialing. Once a choice has been made, that new plant has to be grown in sufficient quantities to be marketed - that will take another year and a half.

The breeders and their products are protected by the plant patenting process. Patent holders get paid a royalty for every plant that is eventually sold. And growers pay a licensing fee to be allowed to propagate a patented plant.

When breeders and propagators team up, Tradenames and Trademarks are born. Often, the name of the branding program is a registered trademark.

One of the best known examples is the Proven Winners® brand. In North America, the brand is owned by two leading plant propagators - Four Star Greenhouse in Carleton MI and Pleasant View Gardens in Loudon, NH. Those companies, together with two licencees in Canada - Nordic Nurseries and Sobkowich Greenhouses - produce the annuals sold under the Proven Winners® name. Wholesale growers then “finish” the plants and distribute them to re-wholesalers or to retail garden centers.

Other partners include Spring Meadow Nurseries (producing flowering shrubs) and Walters Gardens (producing perennials and succulents).

Another brand is Bailey First Editions® - that brand encompasses First Editions®, Endless Summer® and Easy Elegance®.

Some breeders take a different route like Tony Avent at TERRA NOVA® Nurseries Inc. They not only breed plants but are also tissue culture propagators and growers.

From the Terra Nova website:

Our greatest claim to fame is the popularizing of new Heuchera varieties that emphasized foliage, not flowers. …TERRA NOVA®is also the world’s most prolific breeder of new Coleus selections, and has introduced new selections of Tiarella, Heucherella, Agastache, Coreopsis, Sedum, Kniphofia, Penstemon, Nepeta and Leucanthemum.

We hold more than 700+ active plant patents in the United States and Europe, and have introduced over 1,000+ new plants, including some developed by others. To drive this pace of constant innovation, the nursery has invested … in plant research … and built a team of top-notch in-house breeders.

They go on to say:

… (After continuous growth) …the owners of TERRA NOVA® decided to start licensing their introductions to other growers in the United State. It was a way to keep market share and allowed the company to reduce freight costs, particulary to the East Coast.

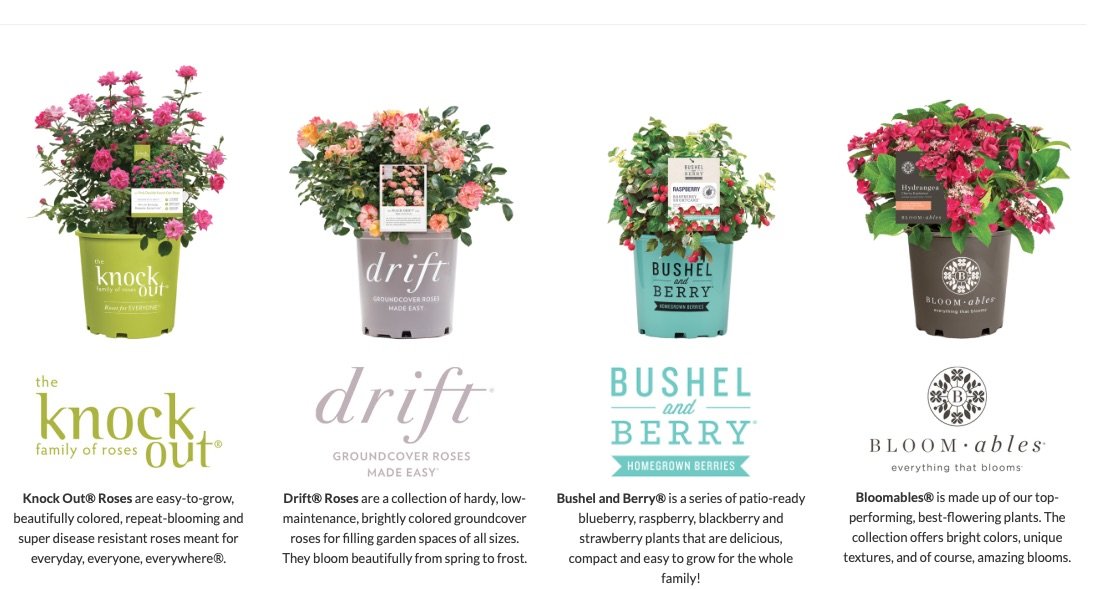

With larger brands came both marketing names, as discussed in my last post, and also aggressive marketing.

America is all about marketing - attention-getting, sometimes colored pots, alluring pictures, cute names, clever tag lines, widespread advertising are all things that increase market share for these brands. The branded plants are patented - they cost more because of royalties.

All the links in the supply chain have to decide which patented and/or brand name products to work with.

Propagators and growers have to license the plants and use the branded pots. Re-wholesalers and retail garden centers have to pay a premium if they want to sell those plants. And we landscapers and landscape designers have to charge more or make less profit when royalties are charged. Independent garden centers have to take into account their sales volumes when they decide what they can afford to bring in. But they also have to balance the “popularity” of branded materials. The customer may say they want Leucanthemum X superbum ‘Banana Cream II’ because they read it was the “best” Shasta Daisy. The garden center has to choose whether to potentially expand their customer base to include people swayed by marketing programs who want the “latest and greatest” versus keep costs low by bringing in non-branded or non-patented Shasta daisy cultivars.

I am not a fan of Shasta daisies - I don’t think I’ve ever planted any since I started my own business. But I attended a webinar on new plants for 2022, and ‘Banana Cream II’ was one of the Proven Winners plants that was being touted. And I asked myself - why? What’s new about it?

This is information from the Patent Application for ‘Banana Cream II’.

BACKGROUND OF THE INVENTION

The original Leucanthemum x superbum, or Shasta daisies, were bred by Luther Burbank in the late 1800's as a cross between Leucanthemum maximum and Leucanthemum vulgare with Leucanthemum lacustre and Nipponanthemum nipponicum. The new plant, Leucanthemum ‘Banana Cream II’ originated from a planned breeding program of the inventor at a wholesale perennial nursery in Zeeland, Mich., USA. The new Leucanthemum was a single plant selected from a group of seedlings from a cross on Jul. 15, 2015 between ‘Sante’ U.S. Plant Pat. No. 19,829 and ‘Banana Cream’ U.S. Plant Pat. No. 23,181. …

BRIEF SUMMARY OF THE INVENTION - (This is the part of the patent application where the new plant is compared to other cultivars)

…The new plant, Leucanthemum ‘Banana Cream II’, is most closely compared to Leucanthemum ‘Leumayel’ U.S. Plant Pat. No. 19,242 and ‘Banana Cream’, ‘Cream Puff’ U.S. Plant Pat. No. 30,074, ‘Snowcap’ (not patented), ‘Marshmallow’ copending U.S. Plant Patent Application, ‘Goldfinch’ U.S. Plant Pat. No. 24,499 and ‘Real Goldcup’ U.S. Plant patent application Ser. No. 17/377,371.

They go on to describe how Banana Cream II is different from other cultivars, and list its unique qualities - which include more flower power and a shorter vernalization time to make it easier to grow.

This is how Banana Cream II is being marketed:

So I ask myself …. is this a “better” Shasta daisy? Would I want to use it, and if so, where? Think about where we designers would have “traditionally” used shasta daisies - somewhere where we wanted a tall expanse of daisy-looking clean white flowers. The middle or back of the border. Qualities that would make a “better Shasta daisy” from my point of view would be a cultivar that didn’t have to be deadheaded, or if it did then at least it would re-bloom. A more compact variety would also make it more versatile for me. But considering that Shasta daisies have been around for literally centuries, they are garden classics. IMO they’re not supposed to be yellow. There are plenty of other flowers that are yellow. There are far fewer that are pure white that deer don’t prefer.

Leucanthemum x superbum ‘Becky’ is considered to be the “standard” Shasta daisy. it was named the Perennial Plant of the Year in 2003 and is NOT patented. That means it’s cost effective for propagators, sellers and landscape designers.

This is what we think of when we think of Leucanthemum.

‘Snowcap’ is a more compact cultivar of Leucanthemum - it is not patented either.

This is ‘Cream Puff’. This patented plant is described as having “…the best of both worlds: lemon yellow buds that open to cream flowers and also a tight, compact habit. …This beauty will bloom for many weeks starting in early summer, and deadheading will encourage rebloom. …As an added bonus for growers, 'Cream Puff' does not require vernalization to bloom. We have observed rebloom late summer through fall with deadheading.”

I would say this qualifies as a “better” Shasta daisy because it will re-bloom after deadheading and the lemon-yellow flower buds add a touch of pizzazz. The flowers still look like Shasta daisies though.

Other cultivars seem farther and farther away from looking like a Shasta daisy to me.

‘Marshmallow’

‘Freak’

‘Sante’

‘Banana Cream II’

‘Goldfinch’

‘Real Gold Cup’

‘Real Charmer’ - are you kidding me?

THIS is what the “real thing” actually looks like!

If there are pollinators out there who have co-evolved with Shasta daisies, I think we should give them something that looks like this.